April 08, 2020

Looking Beyond the Storm: An Interview with Jim Gilliland

As the extraordinary first quarter of 2020 drew to a close, we sat down with Jim Gilliland, our President, CEO, & Head of Fixed Income, to get his views on bear markets, recessions, and opportunities.

Leith Wheeler (LW): As a starting point, how do you put the current market correction in perspective? Are we headed for a recession?

Jim Gilliland (JG): Probably the first thing people consider when they're looking at a market correction is something called the “peak-to-trough” move. So, what was the highest level of the stock market immediately preceding the correction and then what was the lowest level in the stock market correction? That type of analysis is really challenging to do when you're in the time period such as now where you don't know whether you're through it. There's a fair amount of uncertainty in terms of where we go from here.

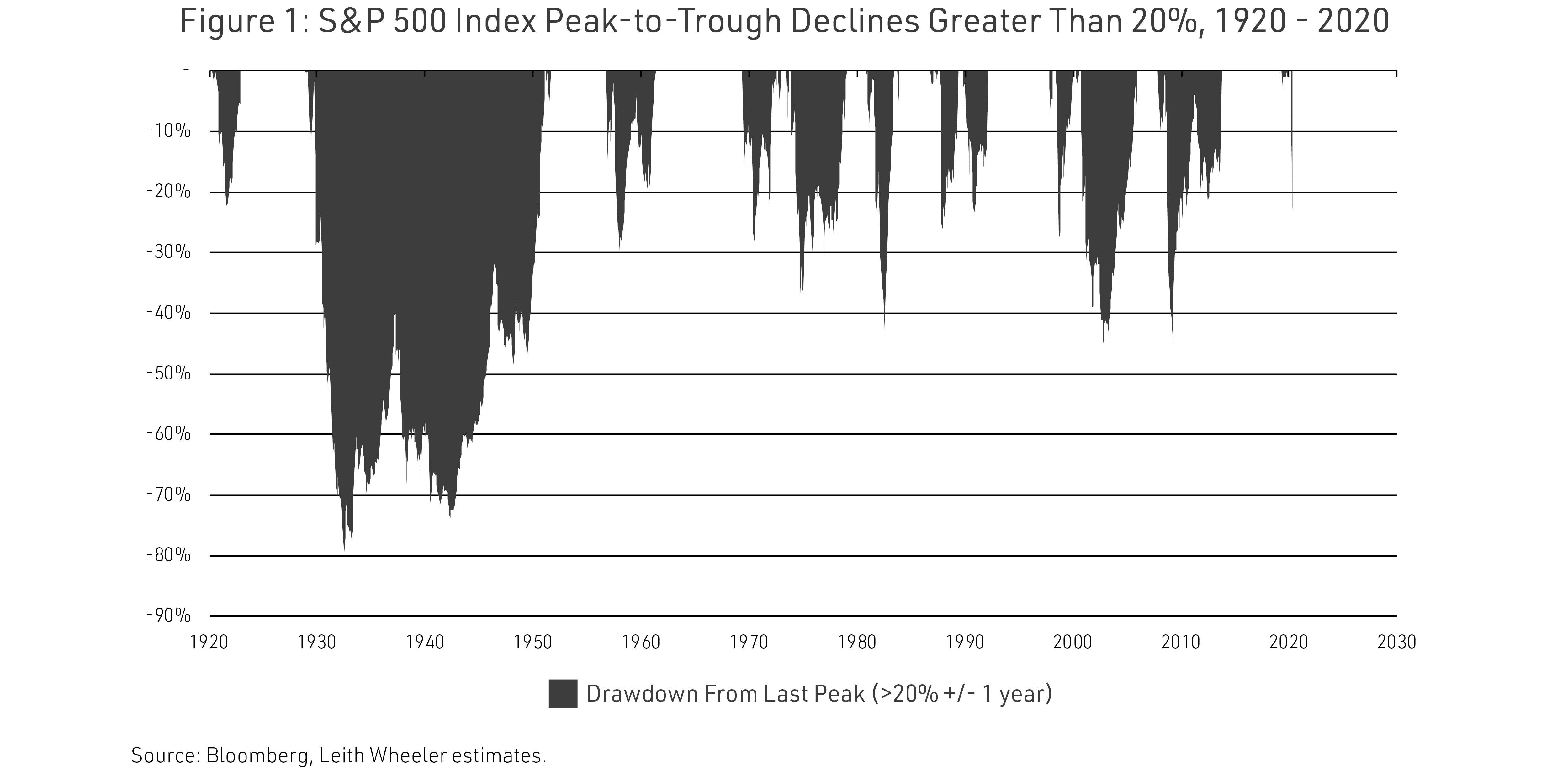

But if you look at the decline from the peak in the market earlier this year to what is the current trough, which was Monday, March 23, it's about a 35% decline in the overall US equity market. While this is undoubtedly a significant fall, the peak-to-trough decline sits around the average of major corrections of more than 20% since the 1950s. See Figure 1.

From an economic perspective, if you go back over the last 100 years, that type of decline would typically correspond to periods where a recession was soon to follow. The times where it was a deeper recession, you would tend to see a market correction more in the 45% range. The Great Financial Crisis of 2008-9 was unique in the post-Great Depression era, in that markets fell closer to 55 to 60%.

A recession is typically defined as two quarters of negative economic growth. Given the stoppages that we've seen due to COVID-19 stay-at-home policies, it's pretty clear that we're going to see two quarters of sequential decline in economic activity. So I think it's fair to say at this point that we are in a recession.

LW: Do you have any sense at this point of the severity or length of the recession?

JG: It’s important to note that what we're seeing now is a recession initiated by public policy. So this isn't like the recession we saw in the early ’90s, which resulted from an excess of debt accumulation, or the one in the early 2000s, that followed the popping of the excess investor hubris of the tech bubble. Even the Great Financial Crisis (GFC), which is generally remembered as taking place in 2008-9, started about 18 months earlier as individuals began defaulting on their mortgages. So while the capital market response was concentrated, the economic lead-up was longer.

This is different. Three months ago, consensus views forecast stable global economic growth and then very suddenly, economic activity all but stopped. And now the factors standing in the way of an economic recovery are public health, and public policy. A resolution of the COVID-19 crisis will therefore be a function of governments’ ability to lead, populations’ willingness to trust in and abide by quarantine recommendations, and ultimately, of course, scientists’ ability to find a cure.

LW: How effective do you expect central bank monetary policy and government fiscal aid to be in dampening the economic impact of COVID-19? Are there limits to what Canada or the US can do to help our economies recover?

JG: We have seen central banks provide a much quicker and much larger response than in 2008-09. Part of the reason is that the current crisis doesn’t present central bank governors with the same perceived “moral hazard” conflict as back then. Today the goal is to ensure good companies don’t fail because they can't get financing… as opposed to the GFC, when they were propping up banks whose business models had too much debt and whose problems were considered by many to be largely of their own making. So today you have central banks saying, “whatever it takes to be able to support well-functioning credit markets” and – it’s early days – but their efforts do appear to be prompting some early improvements to credit markets, much akin to what we've seen in other credit crises or credit contractions.

On the government side, it's a little more challenging. The reason is there isn't a playbook of how to effectively provide fiscal stimulus after an event such as this. In 2008-09 you saw policy makers trying different things because they didn't have a roadmap of how to support the economy in the wake of something as nearly catastrophic as the GFC. We're seeing that same type of experimentation with different types of policies and different types of support – to help both companies and individuals – today.

The overall stimulus numbers in the US are pretty staggering: $2 trillion, with the potential for another $4 trillion to support credit markets. That creates $6 trillion in an economy of about $20 trillion – a significant amount of fiscal stimulus. Despite these large numbers, though, it's unlikely the stimulus will hit every point of dislocation and every industry and every company that has been affected in a uniform way. And so really the questions from an investing perspective are, is it enough? And is it in the right spots so that, once we get through this, companies and economies will be able to start functioning properly again?

LW: Do you think we'll see negative rates in Canada? And if so, what would it take to get us there?

JG: I think it's unlikely that the Bank of Canada or the Federal Reserve sets interest rates at below zero due to the experience of other central banks, mainly in Europe, that found the downside of having negative interest rates were probably more powerful than the stimulative effects. But I think from an investor perspective, probably the most important takeaway is that we most likely will see interest rates remain low and stimulative for some time to come. That likely means close to zero in terms of short-term rates and in the 1% range beyond that. It's unlikely that monetary policy will try to normalize [i.e., rates won’t likely start to rise again] until we're really through the uncertainty of the pandemic, which most of the experts agree is most likely 12 to 18 months away.

LW: Turning to the markets, where are the most vulnerable areas and how are we handling our exposures to them across client portfolios?

JG: The most vulnerable companies are the ones with the greatest uncertainty... and the source of that uncertainty in this particular slowdown is the exposure to public policy governing COVID-19 isolation measures. So you can think of anything that requires individuals to group together, anything that requires people to travel. These are areas that will see public policy put constraints on their businesses, not just for the next several weeks, but potentially the next several months, or until we have some type of vaccine.

We have analysed our Canadian equity portfolio and split holdings into three categories of perceived levels of risk. This categorization allows us to manage how and where we are taking risk in the portfolio, to ensure we are capitalizing on the return opportunities out there, but in a way that controls the overall exposure of the portfolio. In practice, it frees us to buy some names in the highest-risk / highest-return category, knowing that all of our investments are not in that category.

Before going into that, it’s maybe worth taking a second to define what we mean exactly by “risk.” Risk is the potential to win or lose something of value in the future. Stock prices may go up, or they may go down; bonds may get retired at maturity, or the issuer may run out of cash and default. “Uncertainty” is the condition of not having knowledge about those future events. It’s the fog that investors operate in to varying degrees at all times. Right now, with the extraordinary conditions of the pandemic, the fog is much thicker than usual.

Our three risk categories include those with the highest degree of uncertainty, which are those that are the most impacted by it; those with medium uncertainty, where it's pretty likely that over the next say, three, six, nine months, their business will resume unconstrained, and that they'll be able to get back to some version of normal without significant constraints. And then those where you have the least uncertainty where, even in the current climate, they'll be able to operate pretty much at full capacity.

LW: I imagine as well that the risk assessment includes looking at companies’ debt and cash flow levels, and thus their ability to maintain operations through the various scenarios?

JG: Definitely. While we always do extensive balance sheet analysis of the companies we own, we have been performing additional stress testing to determine how our companies would fare if they received no revenue at all for a number of months or longer.

The key questions we’re asking today are: when do those company earnings return to normal and when they do, what is that “normal”? Also, when we're forecasting a company's normalized earnings, it's not just a question of what their business looks like in three to five years, it's also the path that it takes to get there. So a very important question is, do they have the liquidity, the financial flexibility to reduce fixed costs so that they can survive a slowdown in sales, or the credit lines to ensure that their business is able to withstand the disruption? The level of uncertainty regarding the path back to normal therefore also impacts a stock’s risk.

LW: Given that, where are you finding the best opportunities right now, across the entire risk spectrum from equities to bonds and elsewhere?

JG: You know, when we look from a balanced fund perspective, what's clear in the month of March was that the bond markets – specifically, credit markets – had a harder time accommodating liquidity demands than the stock market. [Liquidity refers to the volume of trade, and it affects how easily you’re able to buy or sell a stock or bond. Illiquid markets mean buyers have to pay more, and sellers have to accept less, to get trades done.]

Even though the stock market was down 25%, most days you had pretty good liquidity, whereas in credit markets, that wasn’t always the case. The reason that context is important is that now that liquidity is starting to come back to credit markets, you can definitely see pockets in credit that were more dislocated and so represent better value than what you might find in similar stocks. The baby was thrown out with the bathwater, but now the better-quality names are recovering ground – so we are looking hard at credit markets and high yield bonds in particular.

The equity and bond teams work very closely to understand the debt profile of each company –upcoming maturities; investor appetite for new issues; covenants in place for loans, lines of credit or debentures… and ensuring that the companies that we own on behalf of our clients are the ones that are best situated to offer the right levels of reward given the uncertainty we’re faced with.

I'd say that our work on the stock side is more bottom-up focused than top-down. We’re looking at individual companies to ensure that we understand the business model and financial flexibility, to ensure we're getting fairly compensated for the level of uncertainty. One of the companies we have followed (and owned) for a long time is Brookfield Infrastructure Partners (BIP). This is an example of a company that has demonstrated a strong ability to generate real value for shareholders by sourcing excellent deals on competitive terms, and then improving the assets it invests in. That’s in “normal” periods. As we look through the opportunity set today, BIP stands out as an excellent investment because not only are its businesses – infrastructure assets – less exposed to COVID-19 disruptions, its price has fallen, in our view, to compelling levels.

LW: It can be an emotional ride going through markets like these with equities down and investors seeing negative returns on some of their fixed income investments for the first time in a long time. What are the most important things that individual investors should keep in mind when they're navigating these types of markets?

JG: Probably the most important aspect to keep in mind is to hold the course and to ensure that you stick to your discipline, as we have over the last nearly 40 years through multiple market corrections… whether it was ’87 or ‘94 or ’98, or 2001-02 or 2008, or even some of the volatility we saw with 2011, 2015, and late 2018. And the one thing that is absolutely consistent across each of those is that every time it's slightly different. And because it's slightly different, there's always a tendency when investors are in the middle of it to say, "Yeah, I would like to stick to my discipline, but I can't because this time it's different because of X, Y, Z." And invariably what you see through each of those times is that not sticking to their discipline is what ends up costing them.

So… stay the course, understand that these cycles do occur, and that relative to other types of uncertainties such as what was experienced going into the Great Depression – where you had vast banking collapses, where you didn't have a social security system, you didn't have Medicare, you didn't have any of that safety net to be able to support the economy – this type of event that we're going through has a reasonably defined end date. At some point in the next 12 to 18 months it's pretty likely that we're going to have either some type of vaccine or herd immunity to be able to move back to more normal functioning. And you've got a government who is highly supportive of ensuring that the industries and individuals that are dislocated can get back on their feet.

Relative to each of those things, 100% it is different. It affects people's lives so it's much more visceral and it's much closer to the heart. But from an economic perspective, it's one that you can see a path through if you stick to your discipline and ensure that the investments that you are holding, are the ones that have the right balance of risk and reward for the uncertainty that you're taking on.

Recent Posts

- Resources for Reconciliation

- Leith Wheeler: Investing in Women

- WEBINAR: Leith Wheeler in Québec

- In Conversation with Julia Chung: Advice for Your Golden Girls Era

- Leith Wheeler Establishes Montréal Office, Hires Industry Veterans Eric Desbiens and Denis Durand

- VIDEO: Leith Wheeler Outlook 2025

- WEBINAR: Home Country Bias

- Section 899: A New Cross-Border Tax Threat for Canadian Investors?

- Leith Wheeler Explainer Series: Trade Deficits

- The Leith Wheeler Podcast Playlist