December 22, 2023

Leith Wheeler Explainer Series: The Dividend Debate

Dividends are great, but investors should beware of mistaking (just) a big yield for an investment opportunity. All that glitters on the Christmas tree is not gold. Let me explain.

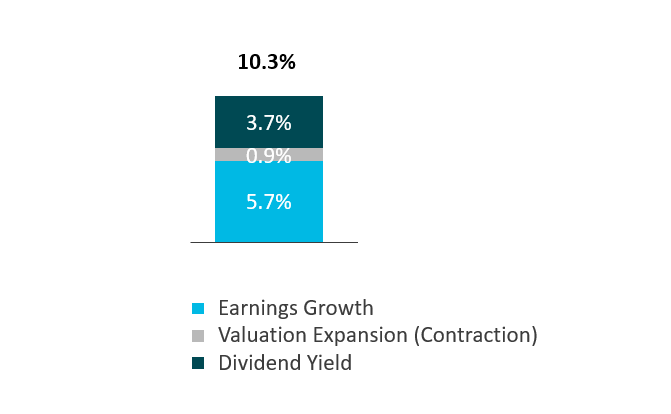

Dividends undoubtedly represent one of the core elements of long-term total equity returns. It can range by company, but as Figure 1 shows, the contribution of dividends to the return of the S&P 500 over the past 85 years has been 3.7%, or 36%.

Figure 1: Components of Stock Market Returns (S&P 500 Index) for 85 years ended Sep 30, 2023

Is this a good or bad thing? Is it better to receive dividends or for the company to reinvest the cash in the business? The answer to these questions is… it depends. Let’s have a look at the pros and cons of dividend payments – for corporations and for investors.

The Pro Case for Dividends - Corporations

Profitable corporations have options when allocating profits. They can reinvest them in their business to help grow them by, for example, buying more equipment to make more widgets. They can buy back and retire their shares, which boosts earnings per share for the remaining shareholders (we covered this concept in our recent article about ROE). Or they can return the money to shareholders in the form of dividends.

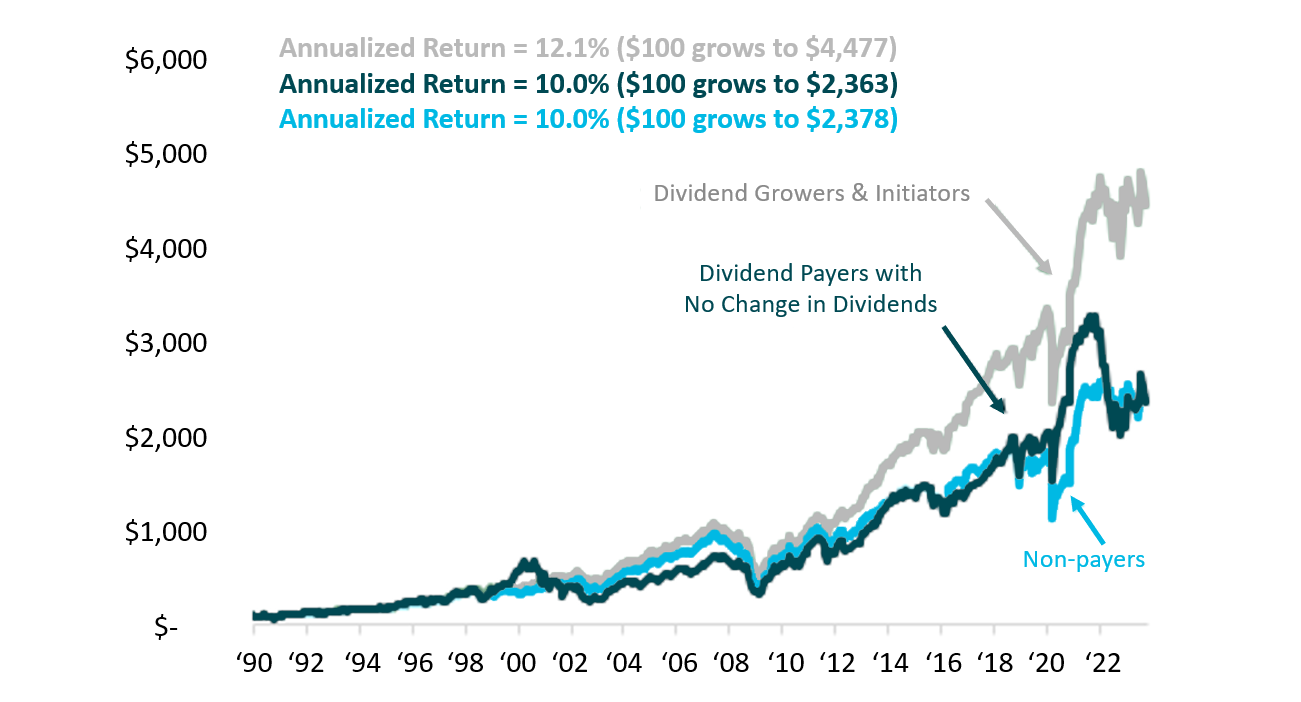

Growing businesses can also increase their dividend and companies with growing dividends, over time, tend to warrant higher share prices. See Figure 2, which shows the outperformance of companies that initiate and/or grow their dividends over time, relative to those with a flat or non-existent dividend policy.

Figure 2: S&P 500 stocks, sorted by dividend policy, Jan 1990 – Sep 2023

There are a couple of things worth noting with this chart beyond the implications of the attractive grey line. One, growing dividend payments are the result of a) growing earnings; b) a growing payout of earnings; and/or c) both. I’ll cover the potential downsides of the payout ratio below, but it’s possible that part of the stock price growth is a reflection of investors’ faith in management to continue growing those earnings.

And two, it’s important to note that some fantastic businesses pay little to no dividends. They typically are fast-growing businesses, often in newer, potentially riskier industries, that need every penny of profit earned to be re-invested into the business to fund growth.

The Pro Case for Dividends – Individual Investors

For taxable investors, dividends are attractive as they are typically paid quarterly, reliably (companies are loath to cut dividends as it signals weakness), can grow over time, and can receive favourable tax treatment via the Canadian dividend tax credit.

The receiver of the dividend also gets to decide whether to allocate the cash to personal consumption or re-investment. The benefit investors have over corporations here is when a corporation repurchases shares, they only have one option (their own) whereas the investor can reinvest in the issuing company, or another.

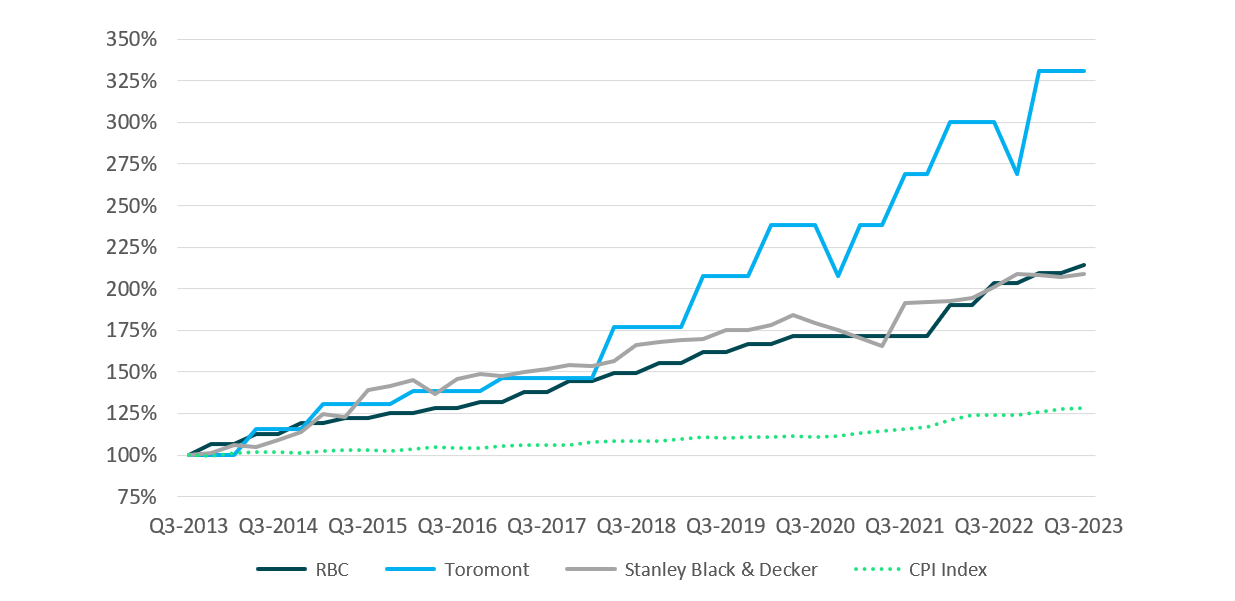

Equities in general tend to be good hedges against inflation – the idea being that quality businesses will grow their earnings (and ideally, their dividends) as the economy grows, in excess of the rate of inflation. In Figure 3, we’ve shown examples of a few companies that have long track records of growing dividends. Toromont and RBC have been core holdings in our Canadian equity strategies for decades.

Figure 3: Dividend Growth of 3 Companies Versus Inflation, 10 Years Ended Sep 30, 2023

The Con Case for Dividends - Corporations

Investors have to trust the management teams of businesses in which they invest to appropriately allocate profits but unfortunately, this doesn’t always happen.

Time to let go. When businesses mature they can hit a point where the best thing for investors is to distribute as much of the excess profits as dividends as possible, because the company just can’t grow fast enough anymore. Unfortunately, sometimes due to poor management, or possibly due to compensation arrangements that incentivize management to continue seeking growth in spite of the headwinds, excess profits continue to get earmarked for lower and lower-return projects, when they would be better deployed by investors into other opportunities. This is the scenario where you’d hope that dividends would rise but they don’t.

Keep stoking the coal. Alternatively, some management teams go in the opposite direction, paying out too much profit as dividends and not re-investing back into the business, to the point that the business cannot support itself. In extreme cases, some can even take on debt to fund their dividend policy. The market has a way of catching up with these businesses over time. When profits start to weaken due to lack of investment, dividend growth has to taper off and ultimately, the share price will falter.

At a macro level, when enough investors want something, the investment industry tends to find a means to deliver it – and sometimes things can get out of hand. One example was the business / income trust craze that took place in Canada about 20 years ago.

Case Study: Canada’s Business / Income Trust Craze

Back in the early 2000s, Canada had a mini bubble related to dividend-type income securities. Income trusts, which had historically been more the domain of energy companies, started popping up in consumer, industrial, and other sectors as companies that had historically been listed as common shares were converting en masse to the income trust structure. Why? Because these entities could take a hatchet to their tax bill, and cash-hungry investors were according these structures higher valuations – which made both management teams and existing unitholders happy. The trouble was that otherwise-growing businesses with no business distributing huge percentages of their profits back to investors were suddenly committed to this game. Seeing the tax leakage (and presumably, the growing dysfunction in markets) the government ultimately intervened – but given more time, it’s likely we would have seen either failures or mass migrations back to the share structure.

The Con Case for Dividends – Individual Investors

One wrinkle in the “tax benefit” argument is that not all dividends are created equal. “Eligible” dividends get the tax credit; non-eligible ones do not. Foreign dividends can in some instances also attract higher withholding taxes.

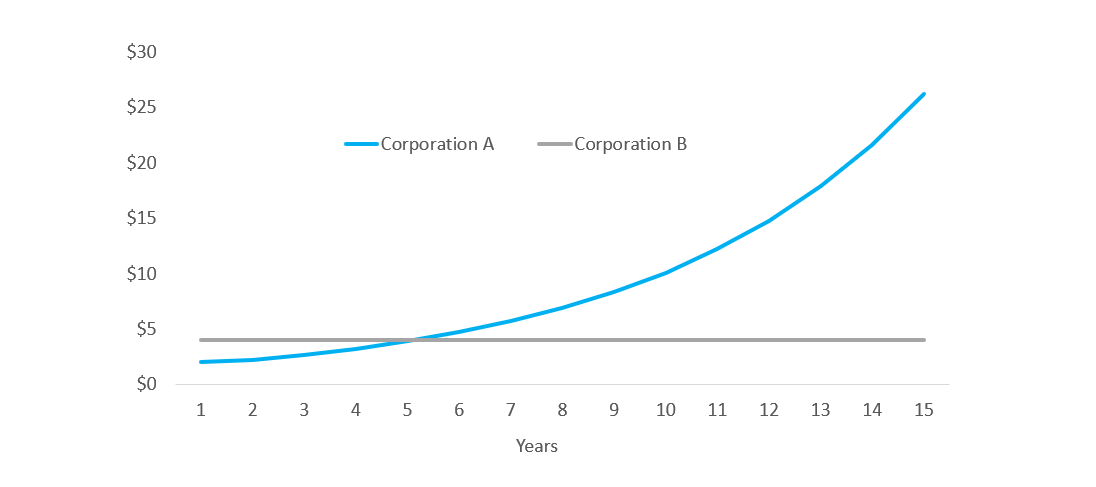

Investors should also understand that when it comes to dividends, more (today) is not always better. Even ignoring the benefit a rising dividend provides to the share price over time (from Figure 2), it’s important to remember that a juicy dividend yield from a mediocre company today is inferior to a modest-but-growing-dividend company over time.

See Figure 4, which illustrates how an investor will receive more dividends over time buying Business A with a starting dividend yield of 2% that grows at 20% per year, than Business B with a starting dividend yield of 4% that does not grow. Over 15 years, the aggregate dividends received from A would be $144, to B’s $60 – and remember those dividends can be reinvested each year to compound up even more with stock price growth.

Figure 4: Hypothetical Dividend Payments from Zero-Growth and 20%-Growth Companies (Share price today: $100)

The unfortunate reality is investors and sometimes their investment advisors are attracted to the shiny bobble on the Christmas tree – in this case, the big fat current dividend. The industry feels they should be able to navigate between the good and bad actors while investors, acting as humans do, focus too intensely on the short-term.

At Leith Wheeler we focus on total return of our investments, which includes both capital appreciation and dividends. Instead of looking for the fattest yield, we focus on businesses with a high level of profitability with low variability and a modest payout ratio (i.e., they re-invest materially back into their businesses). We analyze how well businesses can sustain their dividends, and prioritize companies with a long record of growing them. We’ve found that over time, this approach works the best.

If you’d like to learn more about how we invest in equity markets, please reach out.

Recent Posts

- Resources for Reconciliation

- Leith Wheeler: Investing in Women

- WEBINAR: Leith Wheeler in Québec

- In Conversation with Julia Chung: Advice for Your Golden Girls Era

- Leith Wheeler Establishes Montréal Office, Hires Industry Veterans Eric Desbiens and Denis Durand

- VIDEO: Leith Wheeler Outlook 2025

- WEBINAR: Home Country Bias

- Section 899: A New Cross-Border Tax Threat for Canadian Investors?

- Leith Wheeler Explainer Series: Trade Deficits

- The Leith Wheeler Podcast Playlist