February 16, 2023

Preparing for the Rising Disbursement Quota for Registered Charities

On December 15, 2022, the federal government passed Bill C-32, the Fall Economic Statement Implementation Act, 2022 (“Bill C-32”), implementing a number of changes to the Income Tax Act (Canada) (the “ITA”). Among these were changes to the registered charity disbursement quota rules, which affect the vast majority of Canadian registered charities in Canada (we’ll refer to them as “charities” for this bulletin). The changes establish a new, graduated disbursement quota and increase the top-end disbursement quota rate from 3.5% to 5%. Because this change has important legal and financial implications for charities, the authors (from investment counselling firm Leith Wheeler and global law firm Norton Rose Fulbright Canada LLP) have partnered to put together this brief summary.

What is a Disbursement Quota?

The disbursement quota is the minimum amount a charity must annually spend on its own charitable activities and/or on gifts to other qualified donees. The term “qualified donees” broadly refers to other charities and certain other categories of tax-exempt entities that can issue donation receipts. Failure to meet the applicable disbursement quota may result in the loss of charitable registration and the application of the charity revocation tax.

While the disbursement quota has been revised a number of times, we will focus on the most recent change. Prior to Bill C-32 becoming law, the disbursement quota for a charity was fixed at a flat 3.5% of the value of all property owned by the charity at any time in the previous 24 months that was not used in its charitable activities or administration. This may include, for example, cash on long-term deposit (rather than in operating accounts), securities, stocks, bonds, mutual funds, GICs, and real estate not used in charitable programs or administration. For the purpose of this bulletin, we will refer to such property as “Investable Assets”.

As a result of Bill C-32, the disbursement quota will remain at 3.5% on the first $1,000,000 (all figures in Canadian dollars) of Investable Assets, and increase to 5% on the portion above that level.

When will this change take effect and which organizations will be affected?

The new disbursement quota rate applies to the fiscal periods beginning on or after January 1, 2023 for all charities registered under the Income Tax Act (Canada). This includes any charities that are designated as private foundations, public foundations, or charitable organizations.

It is worth noting that charities with total Investable Assets valued below a prescribed amount are exempted from the application of the disbursement quota. For instance, a charity designated as a charitable organization has a disbursement quota of 0% if the average value of its Investable Assets during the 24 months before the start of the charity’s relevant fiscal year is less than $100,000. For a private foundation or public foundation, the threshold is $25,000.

How much will be required?

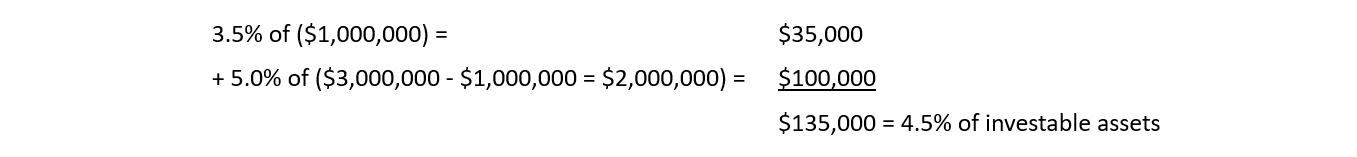

Given it is a graduated formula, charities will be ultimately required to disburse some percentage below 5% of their Investable Assets. For example, a charity with Investable Assets of $3 million would need to disburse:

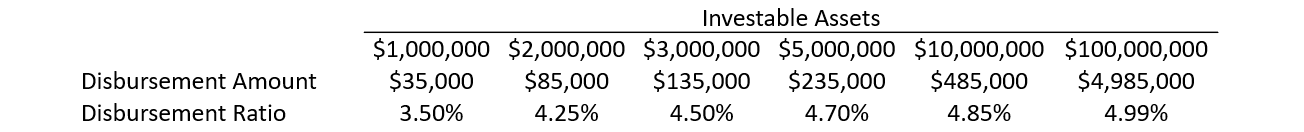

The following table illustrates a few other scenarios:

How is the calculation applied?

The percentage requirement will be based on a rolling, 24-month average fair market value of a charity’s Investable Assets. The 24-month average is intended to provide smoothing when investment markets deliver negative returns, however it should be noted that two years is not a very big buffer, especially in sharply declining markets like the ones we witnessed in 2022.

What could this mean for portfolio asset mix?

With all things equal, a charity would need to generate annual investment returns in the neighborhood of 8-9% in order to meet the 5% disbursement quota without impacting the spending power of its capital balance. We arrive at that figure by assuming inflation settles back to a more normal 2-3% long-term annual rate, disbursements are 4-5%, and administrative costs are perhaps 1-2%.

This is a significant step up from roughly a 6% average annual return the typical balanced investment portfolio delivered over the past 10 years. Higher yields on the bond portion of balanced portfolios today may help deliver higher balanced portfolio returns but it is worthwhile examining your charity’s current asset mix and investment plan to see whether it can deliver on the higher distribution requirement.

Similar to the way an individual can carry forward capital tax losses to apply against future capital gains, CRA has provisions that enable charities that disburse more than is required under the Bill C-32 in a given year (called a disbursement quota excess) to apply that excess to future years. Disbursement quota excesses can be carried forward for five years or carried back one year.

This provision gives charities some breathing room in years in which they need to reduce disbursements to a level below the required rate. In such a case, they might apply previous quota excesses to meet that year’s requirement. In the case where a charity has no quota excesses and falls short, it can apply excesses in the next year, retroactively one year, to remain compliant.

Bill C-32 removes the accumulation of property rule from the ITA, which exempted charities from including certain property in the calculation of their disbursement quota (DQ). As a consequence, Bill C-32 amended the ITA to authorize the CRA with discretion to reduce a charity’s DQ obligation, upon a charity’s request, for given fiscal year. Where the CRA elects to exercise its discretion where requested, its decisions may be made public.

Limitations on a charity’s ability to access or repurpose existing funds

Many registered charities who are concerned about their ability to comply with the new disbursement quota may be tempted to use capital from endowments or other restricted funds. Unfortunately, this is not a viable solution in most cases.

Where a charity has accepted a gift from a donor to establish an “endowment” or in which the donor has clearly restricted access to the gift capital, or otherwise expressed what part, portion or percentage of the gift may be expended over a given period of time, the charity (including its directors and management) have a fiduciary duty to comply with such restrictions on an ongoing basis, indefinitely.

These gifts often use “endowment” language or restrict “encroaching” on the capital of the fund. This language can be in the gift document, deed, agreement, terms of reference or even in communications between the charity and the donor. If it is imposed from the donor (or other external source) and the charity has accepted the gift, it must abide by those terms. Failing to abide by the restrictions in such circumstances could expose the charity to legal liability (and potentially its directors to personal liability).

Often, charities in this situation ask whether they can amend the gift to revise the problematic term. This is only possible where the original gift document includes an express right to amend. The terms of a charitable gift are set at the time the gift is made. Absent an express, documented right to amend the terms of a gift, neither the charity nor the donor can amend or rescind restrictions on access, even when it becomes difficult or even impossible to satisfy such obligations because of administrative, logistical or economic issues.

In such circumstances, a charity’s only recourse to amend the restrictions or to “re-purpose” the gift would be to apply to the court to obtain an order to do so. This can be a time-consuming and costly endeavour and courts are not always willing to exercise their power to amend restrictions simply because a charity has requested it. Legal advice should be sought when a charity wishes to access capital or to re-purpose an existing fund.

The new disbursement quota regime does not remove these restrictions, or allow charities to encroach on funds established by donors as endowments or subject to other restrictions on access to capital. Nor does it provide a right to amend when one does not otherwise exist.

Charities whose only income comes from its Investable Assets will need to consider whether current returns are sufficient to meet the increased disbursement quota, or whether changes to their investment policy statement are necessary to achieve them. Alternately, certain assets may need to be liquidated or changed to a different form of investment to provide a means of meeting the increased disbursement quota. Charities should seek advice from legal and financial professionals to discuss their options and make informed decisions.

Authors:

By Michael Blatchford, Partner, Norton Rose Fulbright

michael.blatchford@nortonrosefulbright.com | 604-641-4854

By Bryan Millman, Of Counsel Norton Rose Fulbright

bryan.millman@nortonrosefulbright.com | 604-6411-4851

Recent Posts

- Resources for Reconciliation

- Leith Wheeler: Investing in Women

- WEBINAR: Leith Wheeler in Québec

- In Conversation with Julia Chung: Advice for Your Golden Girls Era

- Leith Wheeler Establishes Montréal Office, Hires Industry Veterans Eric Desbiens and Denis Durand

- VIDEO: Leith Wheeler Outlook 2025

- WEBINAR: Home Country Bias

- Section 899: A New Cross-Border Tax Threat for Canadian Investors?

- Leith Wheeler Explainer Series: Trade Deficits

- The Leith Wheeler Podcast Playlist