May 16, 2023 | Quiet Counsel | 8 min read

An Ode to Boring: Canadian Banks circa 2023

Banking is best when it is a dull business, devoid of excitement. Unfortunately for some bankers and their shareholders, though, excitement has been running higher than normal lately, resulting in the collapse of a few regional US banks.

There are two sometimes related sources of worry within any banking system: credit losses and a loss of trust. In this edition of Quiet Counsel, we’ll take a look at the role these factors have played in the recent turmoil and address the question on many of our clients’ minds: should we be worried about our Canadian banks?

Visit our website, to download previous Newsletters and read our latest Insights.

Trust

All banks rely on the trust of their depositors that should they need their money, it will be there. But when trust is lost and depositors all want their money back now, there is not a bank anywhere that can deliver it. Why? Because the vast majority of the cash on deposit has been lent out to other customers.

Viewers of It’s a Wonderful Life will recall the iconic scene where George Bailey explains this concept, in fighting to convince Savings and Loan customers not to panic.

CHARLIE: I’ll take mine now.

GEORGE: No, but you... you... you’re thinking of this place all wrong. As if I had the money back in a safe. The money’s not here. Your money’s in Joe’s house... (to one of the men) ...right next to yours. And in the Kennedy house, and Mrs. Macklin’s house, and a hundred others. Why, you’re lending them the money to build, and then, they’re going to pay it back to you as best they can. Now what are you going to do? Foreclose on them?

Source: Daily Script.

This exchange captures the core of the banking business model: borrowing (with a promise to pay it back on demand) and investing (in loans that won’t mature for a long time). For the model to work, faith in the bank’s own credit-worthiness has to persist.

Credit Losses

Banks make money by paying less interest on deposits than they charge for loans they make to borrowers (called the “spread”). This spread compensates the bank and its shareholders for any borrowers unable to pay back their loans. For a prudent bank, these losses are planned for as a cost of doing business and a well-managed bank will diversify its risk so that no single problem area in the economy will create catastrophic losses.

As you can see in Figure 1, in the last 20 years Canada’s six largest banks have generally estimated losses of less than 0.5% per year (with the extraordinary years of 2008 and 2020 still coming in under 0.9%). In other words, 99.5% of loans tend to get paid back through a full economic cycle.

Figure 1: Annual Loan Loss Provisions, 1977 - Present

Despite a recent hiccup in home prices and higher interest costs, we haven’t seen bank customers falling behind on their mortgage payments. More restrictive mortgage lending regulations put in place in recent years, plus strong employment, excess savings, and healthy equity in people’s homes mean the risk of a significant credit problem in banks’ mortgage books is reduced.

Given Canadian banks have limited their exposure to any one type of borrower, industry, or region, they are unlikely to suffer catastrophic loan losses. Further, while a recession would cause a spike in loan losses from current low levels, such a scenario would be part of the outlook for any prudent bank. We see little to worry about from a credit perspective.

Lessons from Silicon Valley Bank

Recently we witnessed the failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB). SVB did not have a credit problem. In fact, it couldn’t make loans fast enough to keep up with the flood of cash its customers kept depositing! Let’s take a look at six failures that led to SVB’s collapse and assess how Canadian banks might compare.

1. Extremely rapid deposit growth combined with asset liability mismatch. SVB’s massive deposit growth should have been matched with a very cautious approach to investing in assets but rather than keep cash handy for any potential customer liquidity needs, they invested in long-term treasury and government agency securities. While this strategy minimized the risk of not getting their money back (eventually), the problem was that these securities rapidly decline in price when interest rates rise. After a year of significant interest rate increases, SVB had amassed losses about equal to their entire equity capital. They were wiped out.

This same issue does lurk to varying degrees on any bank’s balance sheet as loans cannot be called and securities sold fast enough to satisfy all the deposit liabilities. But a bank that understands and manages its deposit base, and controls its growth, would be unlikely to invest as poorly as SVB did in the face

of the huge inflows it saw.

2. Concentrated deposit base. SVB’s customer base was concentrated in one sector of the economy, in a focused geographic area (venture capital-backed

technology companies and entrepreneurs). This meant that when the venture capital taps dried up, SVB’s depositors all began to draw down their deposits at once – something the bank was not prepared for.

Next, fear about possible insolvency triggered an unprecedented spiral: SVB received US$42 billion in withdrawal requests in a single day and another $100 billion were reportedly queued up for the next day.

By contrast, the disparate nature of a Canadian bank’s customer base makes the speed of SVB’s withdrawals unlikely here.

3. Insufficient deposit insurance. Deposit insurance is meant to engender trust and ward off panic by guaranteeing deposits should a bank fail. However, SVB’s very large individual account balances meant that deposit insurance levels were inadequate to maintain trust. In SVB’s case, over 90% of its deposits exceeded the $250,000 coverage available under the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). 1 A well-diversified depositor base where fewer deposits exceed the insurance threshold would have improved trust levels.

4. Regulatory blind spots. Despite being the 16th largest bank in the US, SVB was of a size that meant it escaped many of the regulations and monitoring that the Canadian banks are subject to. For example, there was no monitoring of stress tests around SVB’s expected liquidity needs nor the stability of their funding.

Also unlike the big Canadian banks, SVB was not “too big to fail.” Because of the huge ramifications to the Canadian economy, if a Canadian bank was appearing to falter, it is our view the regulator would undoubtedly step in alongside the government and central bank to restore trust.

5. History of failure. Since the end of 2000, the US has seen over 500 banks fail. Americans, while supportive of their community and regional banks, must live with a different sense of risk when selecting their bank of choice. By contrast, Canada has not had a bank failure since 1996. Perhaps we are complacent, but such complacency may help avoid panic spirals.

6. One call away. The SVB CEO apparently missed a 4 pm cut-off to make a request for emergency liquidity, putting the final nail in his bank’s coffin. 2 In Canada, the regulator can make six phone calls to cover 90% of the industry they oversee.

The Investor Perspective

How do we as Canadians pay for our more highly regulated and concentrated but safer and more stable banking system? Through higher fees, higher borrowing rates, and lower deposit interest, which in turn help the banks generate high returns on equity (ROE).

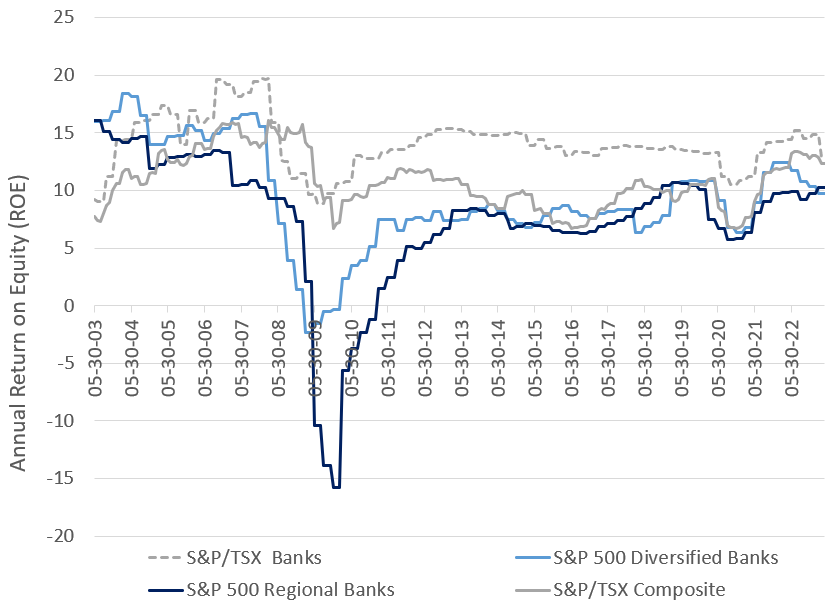

Over the past two years, the domestic Canadian personal and commercial banking businesses of Canada’s five largest banks generated average ROEs above 30%. As Figure 2 shows, over the past 20 years, Canadian banks including wealth, capital markets, foreign operations, and treasury functions have produced superior ROEs relative to US banks and the TSX as a whole. They averaged 14.0% per year.

Figure 2: Annual ROEs of Canadian Banks vs Broad Market and US Banks, 2003-2023

Banks and regulators frequently talk about stress tests. Here is a simple one that could have helped SVB:

- What happens if rates go up? The value of our securities will fall.

- What if the technology and VC businesses are unable to raise capital? They might draw down their deposits as rapidly as they accumulated.

When increasing need by clients to access their cash meets rapidly mounting investment losses, 1+2=0.

Compare that to large US banks, which have produced average ROEs of just 9.4% and US regional banks’ 7.5% over the same 20 years. The S&P/TSX Composite Index averaged 10.8% -- a number itself pulled up by the inclusion of the banks.

What does this mean for investor outcomes? If these superior ROEs are well understood one would expect investors to pay higher valuations to “price in” those better internal returns and thus leave investors to realize a similar investment return to US banks and the broader TSX.

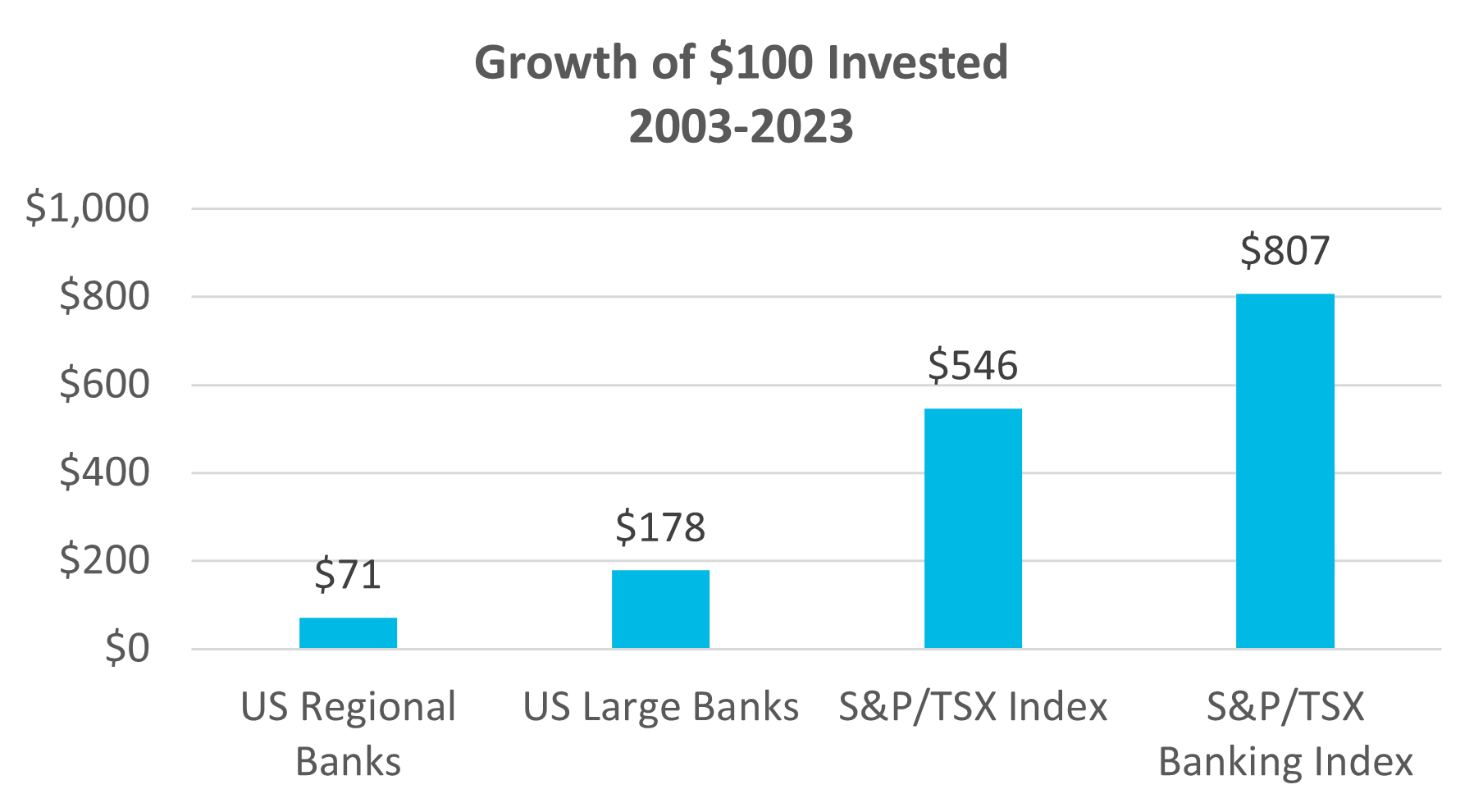

While Canadian banks have tended to trade at a premium in terms of price-to-book ratio versus US ones, as Figure 3 illustrates, investors in Canadian banks have in fact historically earned significantly superior investment returns, growing $100 to $807 in the last 20 years – orders of magnitude above their American cousins, and well ahead of the broader Canadian market

Figure 3: Growth of $100 Invested, April 30, 2003 – April 30, 2023 (Canadian dollars)Source: Factset. S&P 500 Regional Banks Index and S&P 500 Diversified Banks Index represent regional and large cap bars, respectively.

As investors in Canada, we should be thankful for the reminders that US banks offer of the risks inherent in banking. Not only does it keep investors such as ourselves vigilant to the risks, but it also provides for a discounted valuation for our well run, well-regulated, and highly profitable banks. No banking system is immune to the risks of panic and hysteria but the conservative and thoughtful approach of our home-grown institutions give us confidence in their long-term resilience.

IMPORTANT NOTE: This article is not intended to provide advice, recommendations or offers to buy or sell any product or service. The information provided is compiled from our own research that we believe to be reasonable and accurate at the time of writing, but is subject to change without notice. Forward looking statements are based on our assumptions, results could differ materially.

Reg. T.M., M.K. Leith Wheeler Investment Counsel Ltd.

M.D., M.K. Leith Wheeler Investment Counsel Ltd.

Registered, U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.