November 20, 2023 | Quiet Counsel | 6 min read

One Metric to Rule Them All: The Power of ROE

This edition of Quiet Counsel focuses on measuring value creation through the magic of Return on Equity (ROE). In the short term, sentiment can help boost the price the market is willing to pay for a given set of earnings but long term, without a demonstrated track record of being able to grow those earnings, a company’s – and a stock’s – performance will go nowhere. So our investment teams focus on whether businesses have what it takes to create real value, consistently, over time.

What does it take? At its core, it’s about generating consistent, sustainable earnings growth from the cumulative value that’s been created in the company so far:

Net income is the bottom-line profit that a business earns after paying everyone including its staff, its suppliers, its rent, its lenders, and so on; and Shareholders’ Equity is a measure of all the money put into the firm + the money retained in the firm2:

- the cash that was put into the company by the founders and investors in subsequent share issues; and

- the money that was retained within the business over time – i.e., the profits less any dividends paid out to shareholders.

So essentially, ROE answers the question: how much did you grow earnings this period in comparison to what you had to work with?

Margin Growth

A central element of ROE is the profit margin a company is able to generate. Net profit margin denotes how well a company can turn sales into earnings.

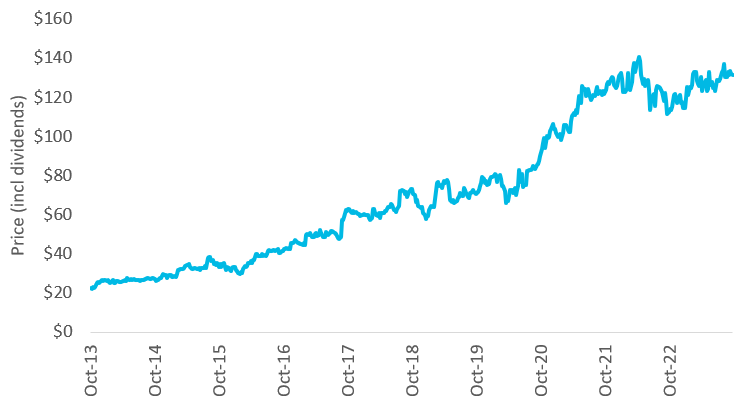

“Margin growth is in my experience the driver of equity returns,” says Dave Jiles, who heads up Leith Wheeler’s Canadian equity team. “If you have growing margins that are sustainable, the stock will follow.” He points to Caterpillar dealer Toromont Industries as an example (see Figures 1 and 2), a long-time holding in Leith Wheeler Canadian equity portfolios that has a demonstrated ability to grow its margins – and generate high ROE and stock price returns.

Figure 1: Stock Performance of Toromont Industries, 2013-2023 (Total Return including Dividends)

Figure 2: Toromont Industries Return on Equity for the Past 10 Years (2013-2022)

Common attributes among companies able to do this well include: disciplined cost containment, a competitive advantage that gives them pricing power, rational industry players, economies of scale that enable them to lower unit costs, and a shrewd ability to deploy capital profitably.

Capital Deployment

“One of the key components to high ROE and Return on Invested Capital3 is the ability to deploy capital,” says Richard Liley, a portfolio manager on the Canadian equity team with Dave. “The companies that really create value reinvest their cash into the business.”

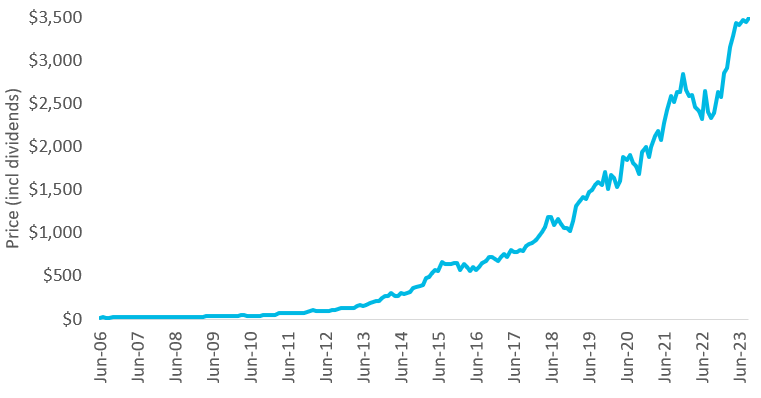

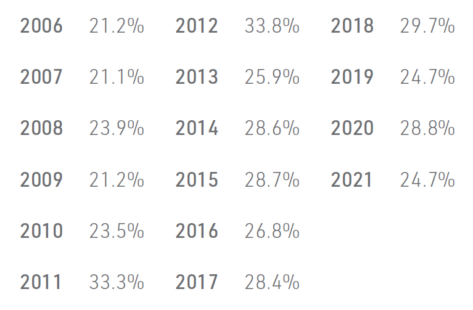

Constellation Software is an example of a company whose management team has a superb track record of doing just that (See Figures 3 & 4). The company’s business model is to buy private software companies and consolidate them. Doing this well – not only identifying quality companies and paying a fair price, but then giving them an environment to continue thriving after they’ve been acquired – is very difficult, but Constellation has proven its merit time and again. Shareholders (like Leith Wheeler clients) who bought on the IPO in 2006 have seen their investment increase by over 19,000% since then, or about 35% per year.

Figure 3: Stock Performance of Constellation Software Since IPO (Total Return including Dividends)

Figure 4: Constellation Software Return on Invested Capital Since IPO (2006-2022)

Canadian banks often get an honourable mention in a conversation about ROE because they tend to reliably deliver ROEs in the mid-teens. But banks are not without constraints. Given their dominance in everything from banking to capital markets to asset management to insurance, Canadian banks can quite simply struggle to find new ways to invest in the Canadian market. “Forty to 50% of the cash they generate is paid out as dividends,” Liley says, because the market is so saturated. “You can’t really force people to take out loans.”

The only logical alternative then is for the Canadian banks to go global in their ambitions, which they’ve all done to varying degrees (and with varying levels of success). Scotiabank for example has paid out the biggest percentage of their earnings as dividends (and so, retained the least for their business). Together with some mixed results from their push into Latin America, they’ve generated the worst results of their peers in recent years.

Shareholder-friendly Financing

One important lever that affects a company’s ROE is the “Shareholders’ Equity” part of the equation. Companies have broadly three options when financing themselves over time: through internal cash flow, by borrowing from a bank or issuing corporate bonds, or by issuing new stock (which increases shareholders’ equity). There is no one good answer to what is best in any circumstance, but the following things can happen when you use each one:

Financing Method | What's Good or Bad About It? |

| Through the cash flow it generates within the business | The gold standard. Earning and reinvesting cash flows within the business is great as long as the projects you are funding generate sufficient return. |

| By borrowing money from the bank or the bond market | There is an optimal level of debt for any company that balances the benefits of lower-cost financing and ROE-boosting preservation of the shareholder base, with the incremental risk of going bankrupt. This is the double-edged sword of leverage. |

| By selling new stock (equity issuance) | If you issue stock to finance mediocre projects, you will slowly erode the value of your shares by diluting (reducing) earnings per share and lower ROE. See Magna example below. |

It’s easy to look at a bond issue and say, “That $100 million bond issue is costing the company 7% interest, so $7 million per year before tax.” But what is the cost of raising that $100 million by issuing new shares?

I think of it this way: if new guests showed up to dinner, how much does the (earnings) pie have to grow so your piece doesn’t have to shrink? In practical terms, management teams often invite new guests to dinner (issue stock) to fund projects – but do the new projects pay off enough so everyone – old and new shareholders – ends up richer?

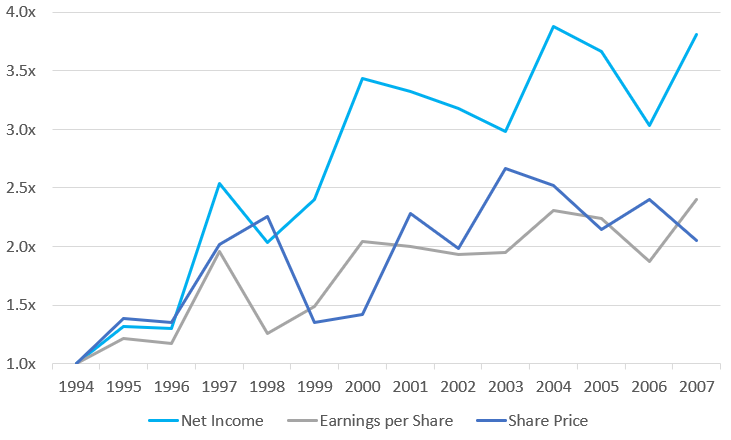

About 20 years ago I covered the auto parts manufacturer and assembler, Magna International (a stock Leith Wheeler has not owned). After getting into some hot water by overleveraging and almost losing the company in the 1990s, founder Frank Stronach opted to issue stock frequently thereafter. He preferred to keep selling off pieces of the company rather than flirt with bankruptcy again. The good news is Stronach did a lot of good things operationally, but all those extra shares out there meant the long-term shareholders kept getting their pie slices trimmed. Figure 5 shows Magna’s Net Income versus its earnings per share (EPS) and share price over that 10 to 15 year period. As you can see, earnings grew (great!) but EPS – and as a result, its share price – grew far slower (less great). This chart shows that for investors, EPS is what ultimately matters.

Figure 5: Magna International Net Income, Earnings per Share and Stock Price, 1994-2007 (Indexed to 1994)

Conclusion

Our analysts agree on this: companies that focus on growing margins, deploy their capital wisely, and prioritize EPS growth are well positioned for attractive ROE – which will, over time, deliver greater value for shareholders.