November 13, 2021 | Institutional Perspectives | 8 min read

Probing Passive, Part I: Panacea or Problematic?

The story of passive investing is one of consequences, both intended and unintended. This two-part series aims to shed light on both, and to highlight the benefits and costs that these instruments carry. We’ll start in British-ruled India in a city overrun with snakes.

Cobras, cobras, everywhere…

As the story goes, for reasons unknown Delhi’s cobra population had spiraled out of control, so the colonial government at the time offered citizens a bounty for each snakehead turned in. It may not surprise you, however, to learn a few enterprising locals decided to turn around and breed cobras who would soon be separated from their heads and turned in for the reward. Call it decapitalism. Once the government discovered the ploy, it ended the bounty system and the now-worthless farmed cobras were mostly released, elevating the cobra population beyond the original level. This is a classic example of an unintended consequence, where attempts to change one thing had an unpredictable (negative) impact on the exact problem being managed.

Central banks’ efforts to stimulate economies against harmful shocks offer another example of unintended (though generally well understood) consequences. Very low interest rates stimulate businesses to borrow and grow, retain and hire employees, and expand the economy. They can also hobble pensions’ funded ratios, lift equity prices beyond rational valuations, and increase investors’ risk appetites. Before our current extreme example, you can look to the dot-com collapse around 2000, which then led indirectly to the Great Financial Crisis in 2008 through a housing boom fueled by low mortgage rates1.

Passive investing, or indexing, was also developed to solve a problem and has experienced some unintended consequences of its own.

Agitating Against Active

Passive investing (or indexing) refers to the investment in a market or index as a whole, rather than attempting to pick the winners and avoid the losers to beat the market. It appeals to investors who believe active investment managers do not earn enough of a premium over market returns to cover their higher management fees. More on that later.

Since Vanguard founder Jack Bogle launched the Vanguard 500 (known as “Bogle’s Folly”) as the first index mutual fund in 1976, the growth of this strategy has only grown in more recent years, parabolically. Active US equity funds’ lead has shrunk from being 6.5x the size of passive in 1998 to parity in 2019 (when $4.9 trillion was invested in each of passive and active US equity strategies).

Undoubtedly, low-cost passive investing has brought benefits to millions of investors by offering a low-cost option for accessing equity market returns, without requiring much homework around manager selection2.

This benefit has accrued to investors and the investing industry itself by largely weeding out poorer quality or overly expensive active options as the spotlight has focused in on not only what returns active managers are generating (net of fees), but also on how those returns are generated. Closet indexers – a term describing managers who tend to build portfolios that look very similar to their benchmark to avoid large tracking error, or blow-ups – have had to answer for their cowardice. Index advocates have rightly decried these practices and asked investors, “Why pay active fees for essentially passive performance?”

Passive is No Panacea

That’s not to say that the passive “industry” is uniformly cheap, and universally appropriate for investor portfolios. As with any successful concept, niche providers have emerged to offer investors exposures to exotic sub-indices, commodities, and other risk assets – sometimes loaded with leverage and carrying high fees. For example, this recent Financial Times article looks at an academic study into US-based thematic ETFs which concluded that as a group they “underperform the stock market on a risk adjusted basis by about 4 percentage points a year for at least five years following their launch.”3 Buyer beware.

The incredible growth of indexed investment products has also created troubling distortions in market activity. Chief among these is the contribution to momentum in the market. Back in the world of perfectly efficient markets, stock prices would gravitate to intrinsic value based on universal agreement on the future of a company’s cash flows. Investors of course do not enjoy universal agreement; this disagreement is what makes a market - when the two traders are active managers.

By contrast, the “buy” or “sell” signals for an index fund manager are solely the prevailing weight of a stock in the index. The trouble arises when a) a stock becomes larger within the index, and so attracts additional buying into it by virtue only of its size, possibly irrespective of its own fundamental quality; and/or b) when the pool of money in aggregate chasing index returns itself becomes large.

Think about the example from above: 50% of the money invested in US equity strategies is now indexed. That means that half of the market is trying to achieve price discovery for all the companies based on research-driven supply and demand for their shares. But fully half of the market is just sitting on the sidelines, waiting to throw $4.9 trillion at the result. The result, as you can imagine, can become a case of the tail wagging the dog: big weights in the index become bigger and bigger due to the virtuous cycle that indexing creates.

The most vivid example of this phenomenon is when small cap stocks are added or removed or even suspected of being added or removed – from a large index like the S&P 500. Institutional scale buying or selling accompanies or precipitates these reconfigurations, to the great benefit or detriment of shareholders in these borderline companies.

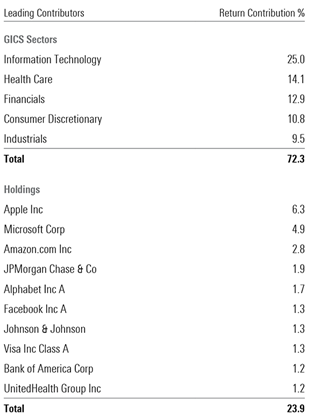

Rising markets have a similar impact on market concentration, but for a psychological rather than systemic reason: people want to keep buying winners... until they are no longer winning. Combine that mentality with the surge in passive investing in the 2010s and it is no surprise that markets rose significantly, and that the gains were centralized in the largest names. Figure 1 shows a history of market concentration, marked by a 5% spike following the energy correction in 2015, and Figure 2 shows how the contribution to total US equity market gains post the great financial crisis were produced by five sectors (72%) and the top 10 names (24%). Current levels are exceeded only by the mania of the tech bubble.

Figure 1: Percentage of Vanguard Total Market Stock Market Index in Top 10 Holdings, Sep 1997 – Dec 2019

Data source: Morningstar Direct

Figure 2: Concentrated Sources of Return within iShares Core S&P 500 ETF, March 1, 2009 - Dec 31, 2019

Data source: Morningstar Direct. Portfolio data for iShares Core S&P 500 ETF from March 1, 2009, through Dec 31, 2019.

Within commodity ETFs, researchers from the universities of Utah and Kentucky published a paper showing that commodities that were added into commodity futures index funds saw immediate distortions in their price, unrelated to market dynamics. Companies that relied on these commodities as inputs faced a 6% increase in costs and a 40% decline in operating profits.

Further, in this paper from Financial Analysts Journal, researchers demonstrate that “[m]ore equity index trading corresponds to … higher return correlations among stocks. Consistent with the accelerating growth of passive trading... equity betas have not only risen but also converged in recent years.” So not only did they find that indexing increased overall market volatility but that there were fewer corners in which to hide when things turned because all stocks tended to move together more. This study was published in 2010 when the authors described the market as $1 trillion in size. Imagine what it looks like now.

Analysts from investment manager Bernstein al so worry that this disconnection between company quality and market price if taken to an extreme may in fact structurally impair the economy. If a given company receives (doesn’t receive) investor money just because it’s large (small), the incentive to innovate and grow for every company diminishes.

Doomsday Soviet scenarios aside, some markets are better suited to indexing than others. Efficient markets theory tells us the opportunities are greatest to “beat” the market (through active management) when there is more information asymmetry that is, when it’s possible to know more than your trading partner about the value of a business. I’m not talking about inside information here just good old-fashioned research in an environment that rewards it.

Take two extremes: the US market and emerging markets. In the US, strict SEC regulations require very high levels of reporting transparency and the massive capital markets machine produces reams of research on thousands of listed companies. Finding and maintaining an ‘edge’ to beat the S&P 500 is very difficult as a result. Investing in South America, Africa, Eastern Europe, or Southeast Asia, by comparison, offers relatively outsized opportunities to uncover hidden gems (and outsized opportunities to make errors).

So indexing is more likely to pay off in efficient markets like the US. Does that mean active management isn’t worthwhile at all?

Please see Part II of our series, entitled “Probing Passive: Part II” to find out.

1In addition to a total failure of regulatory and industry governance.

2It should be noted that not all passive fund providers are created equal when it comes to effectively tracking the underlying index, but that’s out of scope for this discussion.

3Ben-David, Itzhak and Franzoni, Francesco A. and Kim, Byungwook and Moussawi, Rabih and Moussawi, Rabih, Competition for Attention in the ETF Space (July 16, 2021). SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3765...

IMPORTANT NOTE: This article is not intended to provide advice, recommendations or offers to buy or sell any product or service. The information provided is compiled from our own research that we believe to be reasonable and accurate at the time of writing, but is subject to change without notice. Forward looking statements are based on our assumptions, results could differ materially.

Reg. T.M., M.K. Leith Wheeler Investment Counsel Ltd.

M.D., M.K. Leith Wheeler Investment Counsel Ltd. Registered

U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.